MARIA MOLTENI

My work is conceptual, formal, socially engaged, deeply researched, collaborative, contemplative and mystical.

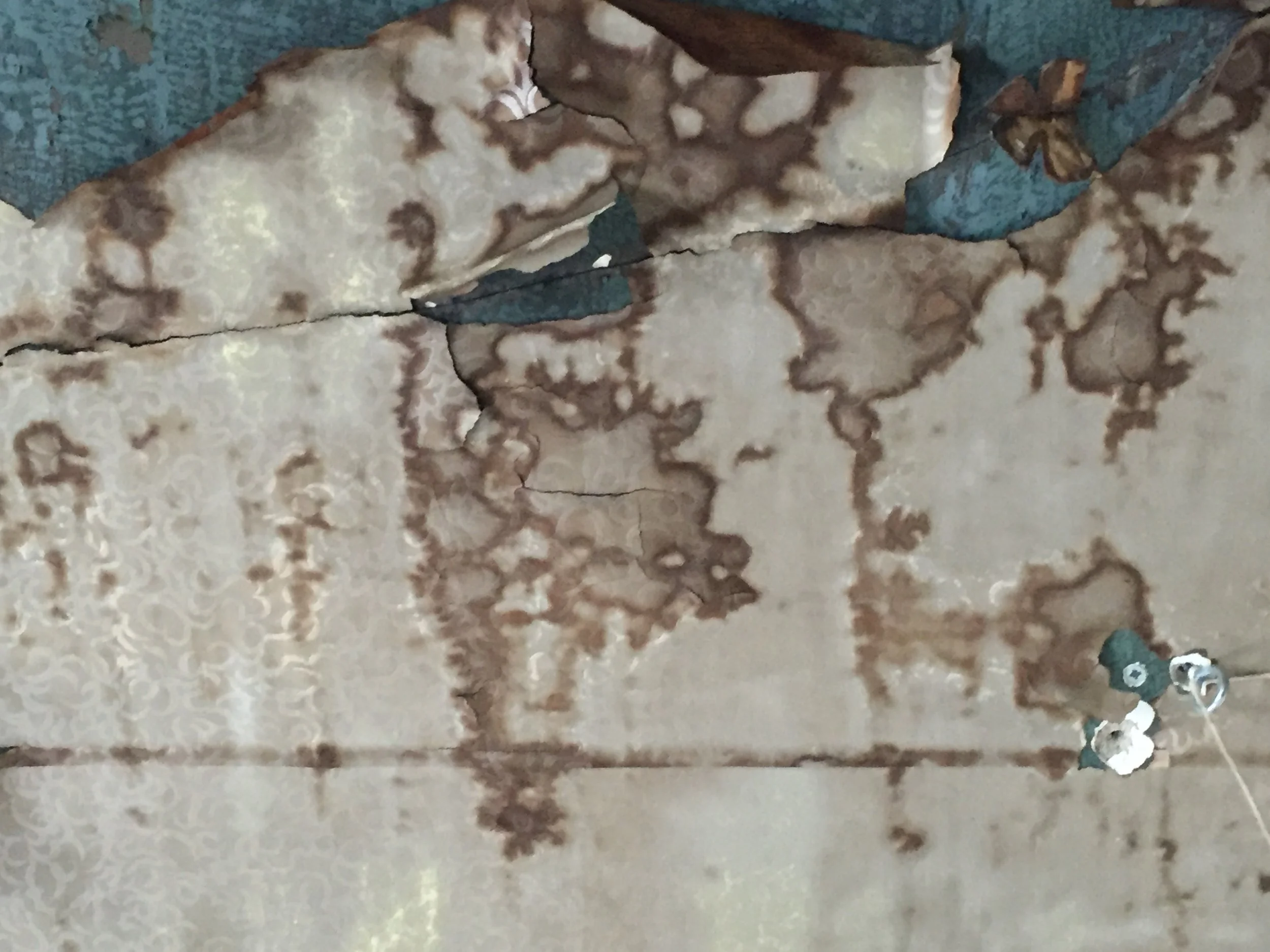

REVOLVING SPECTRUM : The Art of Spiritual Cohabitation / ELSEWHERE LIVING MUSEUM

/

1

2

3

4

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·

·